It was due to my wife Vanda’s encouragement that I wrote this book based on lessons learned from death and a lifetime of service. Having sat bedside with more than 1,000 people while guiding the Zen Hospice Project, and having developed a model of mindful and compassionate care at the Metta Institute, Vanda believed I had something worth saying.

To celebrate our wedding anniversary, she gave me the gift of a writer/editor to help craft a book proposal. That may sound strange if you’re unfamiliar with the publishing process. But basically, if you want to secure a book deal with a traditional New York publishing house, you must first write a proposal, including an About the Author section, marketing plan, complete Table of Contents, short chapter summaries, and a sample chapter. I never would have done all of that on my own.

From the time we began, it seemed, larger forces were at work in making it happen. The universe itself took charge.

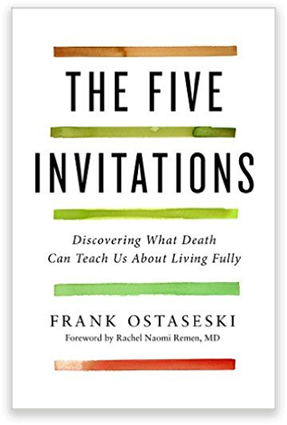

It all happened rather quickly at first. We completed the proposal and signed with a literary agent, then several publishing houses expressed an interest in The Five Invitations. But I asked my agent to give Bob Miller, president and publisher at Flatiron Books, a new imprint of Macmillan Publishers, first dibs. Bob had approached me months before we began the proposal, and we had a good personal connection. I also knew that he had previously published books with friends Jon Kabat Zinn and Sharon Salzberg. He understood that our intention was to share the lessons death and dying have to offer the living. He saw it as a wisdom book. He received our proposal on a Monday morning at 9am. Two hours later, he phoned to say that he was fully committed and would do whatever was needed to publish the book. Apparently, the book wanted to live and breathe.

Still, writing a book is no easy task. For each Invitation, I strove to go beyond the surface level, to engage the reader in an inspiring and provocative conversation centering on fundamental issues such as identity, suffering, and intimacy with our truest self. When I am with a person who is dying, there are no simple answers. Advice doesn’t help. Technique can only take you so far. Similarly, this book could not be about self-help or how-to steps. If it was to have any value, it needed to be real, honest, and personal. Otherwise the reader, like someone who is dying, would sniff out any sentimentality or insincerity.

I reviewed transcripts of old talks and spent hours talking with colleagues. I paid close attention to my dreams. I had conversations with patients I knew, now long dead. I remembered Ngyuen and Connie and Walter. I listened to what they had to tell me, often offering insights I had missed while they were still alive. I wanted to honor the gift they had given in allowing me to share their most vulnerable moments. They were my true teachers. And, when your teacher is in the room, it helps keep you honest.

I wanted to transmit the relevance of the wisdom gained from being with dying in a way that might help people wake up fully to their lives.

As I wrote, I sent chapters to the publisher, shared them with Vanda and several trusted friends. Was I on target? Did I capture the complexities of living in the moment, welcoming everything and pushing away nothing, bringing your whole self to the experience, finding a place of rest in the middle of things, and cultivating don’t-know mind in a way that someone in crisis, someone sitting with a dying person, or someone struggling to define a more purposeful life would be able to relate and apply the wisdom to their own lives?

Chapter by chapter, word by word, it was the slow labor of giving birth. Like accompanying someone who is dying, I had to at times push through immense fatigue, face unimaginable doubt. Sometimes, there was joy and ease. At other times, restlessness ruled. I questioned my ability and motivation. And my own deep clinging, aversion, and habitual patterns presented themselves for review. It was a humbling process. At least a half dozen times during those many months of writing, I wanted to give up. I longed to return to just being with people – accompanying them on their most personal journeys towards death, speaking with actual human beings on retreat, interacting in a way that felt comfortable and familiar. I longed to get out of my office and into the world. I just wanted to be of service again.

But Vanda, my friends, my editor, and ultimately, my own heart’s calling to share the lessons of a lifetime provided the necessary support to allow me to persevere. They helped me see that writing was yet another way of serving.

In the end, I am grateful to see The Five Invitations in print, to hold it, as I imagine others I will never meet will hold it in their hands. I pray that it will serve the world in some small way. Perhaps it will help a few people forge meaningful lives, ones that are more loving, and in the end, free of regret.

I wanted to explore, to make the love, pain, compassion, loss, and forgiveness that can arise around the dying process palpable.

I have done my best to share the collective wisdom of my teachers, loved ones, and above all, the people I have sat with at the time of death or through their grief. I hope that the stories inspire you, as they have inspired me, to live a life that is more raw and authentic, closer to the truth. Now they are no longer my stories. They are yours.

May you enter them wherever and whenever you need. May they help you to appreciate life’s precariousness and fully embrace its preciousness.

Frank

And, when your teacher is in the room, it helps keep you honest. via @fostaseskiTweet This

Leave a Comment