We know that we will die, yet we spend much of our lives trying very hard not to think about it. But is it wise to ignore death? Could we live better if we spent more time thinking about our own mortality?

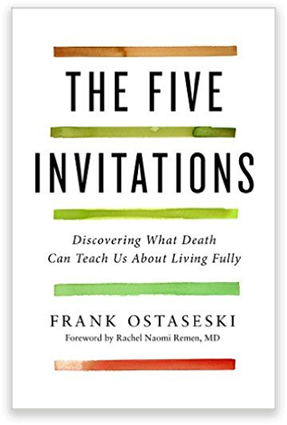

Frank Ostaseski is the author of The Five Invitations: Discovering What Death Can Teach the Living and helped found the Zen Hospice Project’s Guest House, the country’s first Buddhist hospice center, in San Francisco during the AIDS crisis. The center opened its doors to people facing their deaths, caring for them regardless of their background or income. The hospice was unique in its reliance on mindfulness practice as a tool to help people die peacefully.

These days, Ostaseski is director of the Metta Institute, an educational center devoted to end-of-life care in America — and his perspective is badly needed. As Atul Gawande’s best-selling book Being Mortal showed, we’ve done a great job of curing illnesses, managing pain, and helping people live longer, but we still haven’t figured out how to deal gracefully with death.

In this interview, we discuss what Ostaseski has learned from the conversations he’s had with the dying. “For most people,” he told me, “it’s about relationships. It’s about answering two questions: ‘Am I loved?’ and ‘Did I love well?’ So much of what happens around the end of life boils down to those two questions.”

And, he argues, these lessons about what truly matters to humans in the most profound moment of their lives could help all of us live fuller, happier lives right now.

You can read a lightly edited transcript of our conversation below or click on the link to listen to it in full.

Sean Illing

How does Buddhism inform your approach to end-of-life care?

Frank Ostaseski

Buddhist practice, with its emphasis on impermanence, the moment-to-moment arising and passing of every conceivable experience, is an important influence in my life and work with dying.

Facing death is considered fundamental in the Buddhist tradition. Death is seen as a final stage of growth. Our daily practices of mindfulness and compassion cultivate the wholesome mental, emotional, and physical qualities that prepare us to meet the inevitable.

Through the application of these skillful means, I learned not to be incapacitated by the suffering, but allow it to become the ground of compassion within me. Meditation practice develops the equanimity that often allowed me to be the one calm person in a very chaotic situation.

Finally, in Buddhist thought, one aspect of compassion is boundless and all embracing. We might call this universal compassion. Then there is everyday compassion. The compassion that gets expressed in daily life, when we feed the hungry, stand against injustice, change soiled sheets or listen generously to a friend’s broken heart. We may be effective or ineffectual in our efforts, but we do the best we can. These two facets of compassion rely on each other.

Sean Illing

How would you describe the work that you do?

Frank Ostaseski

It’s not so easy to describe, but I basically do two things. One is that I assist people who are going through the dying process, helping them to find their best way of dying.

The second thing I do is teach health care clinicians about how to provide mindful and compassionate care. We want a human face on medicine. We don’t want to just have a technician at our bedside, particularly when we’re dying. Those are the two things I tend to focus on the most.

Sean Illing

What drew you to death and dying? Why do this kind of work?

Frank Ostaseski

When people are dying, they tend to be pretty honest, and there’s not so much nonsense in the room. I like to be around that. I like to be around people when they’re being real. When we’re coming close to the end of our life, we tend to focus on what matters most, and the rest of it sort of falls by the wayside.

Sean Illing

So what’s your goal: to help people manage their own deaths or to help them make peace with it?

Frank Ostaseski

I think death is completely unmanageable. Medicine puts a lot of effort into trying to manage this experience, which is too big in a way, too profound for medicine. I think what we do is we help people do the normal things that any other hospice would do. That is, make sure that their pain is well managed, that their symptoms are under control, that they’re not suffering.

Then we try and find out what really is important to them. For some people, it’s relationships. For others, it’s about looking back on their lives and seeing what legacy they’re leaving behind. For others, it’s about discovering a kindness or forgiveness that they were looking for their whole lives.

I think this work is really about companioning. It’s really about being in a relationship with this person and walking hand in hand with them as they approach their death. I’m not so much guiding as I am companioning, and to be a good companion, I have to do my homework. I have to know what my own relationship is to these things. Otherwise, if I say, “I understand,” the person will sniff out my sentimentality and my insincerity.

Living in the shadow of death

Sean Illing

Most of us try very hard not to think about death, but it still has a kind of tyranny over our daily lives. You seem to think there’s a lot to be gained by staying close to it, however. Why?

Frank Ostaseski

When we come close to the end of our life, what’s really important makes itself known. It isn’t whether or not we have two Mercedes or whether or not we spent more time at the office. For most people, it’s about relationships. It’s about answering two questions: “Am I loved?” and “Did I love well?” So much of what happens around the end of life boils down to those two questions.

If those questions are important then, why aren’t they important to us now? Why should we wait until the time of our death to discover the answers to those or even ask ourselves those questions? That’s the first thing that comes to mind.

The second is that I think that when we begin to keep death close at hand, we understand just how precarious this life actually is. And when we see that … then we come to see just how precious it is, and then we don’t want to waste a moment. Then we want to jump into our life. We want to tell the people we love that we love them. We want to live our life in a way that’s responsible, meaningful, purposeful.

Sean Illing

I think a lot about what I’ll most regret at the end of my life. I suspect it’ll be that I paid attention to the wrong things, to trivial things. Is this common among the people you’ve cared for?

Frank Ostaseski

There’s a lot of talk out there about, “What are the regrets that people have as they come to the end of their lives?” and I think that’s useful to look at. I’m more interested in, “What are the transformations that people make at the end of their lives?” What do they open up to? What do they see about their lives that they didn’t see before?

People often discover at the time of their death that they’re much more than the small, separate self they’ve taken themselves to be. What’s amazing to me is that we take all that we are and shrink it down to such a small story. And then live into that story as if it were true. At the end of their life, people realize they were living in too small a story.

Sean Illing

Philosophers tend to think of death in one of two ways: either it renders life absurd or it gives life its meaning and shape. How do you think of it?

Frank Ostaseski

I think you’re really pointing at something essential here, Sean. We have this term that we use, “later.” It’s very comfortable, this term “later.” It’s always gonna be later. “I’ll get to that later,” or “Death will come later.” I think it gives us a comfortable distance from this experience that’s rather mysterious to us.

Death is not just happening to us at the end of a long road. It’s always with us. It’s in the marrow of every passing moment. I call it “the secret teacher that’s hiding in plain sight” that helps us to discover really what matters most.

Think about every spring, for example, in Japan. Cherry blossoms cover the mountains. There’s a place where I teach up in Idaho where there are these blue flax flowers that come out for one day. They last for one day. Now, what is it about those flowers that is so beautiful? Why is it so much more beautiful than plastic flowers that might last forever? Isn’t it the brevity of their life that helps us to appreciate their beauty?

Sean Illing

Do you think it’s because we are so terrified of death that we can’t face it honestly?

Frank Ostaseski

That’s part of it. We’ve been told some really scary stories about death, and we believe them. That’s why it’s really important to me to tell stories where people discover in the final months, weeks, sometimes moments of their life something really essential about themselves and their nature.

This is from people, by the way, not spiritual sages. I’m talking about ordinary people, oftentimes people who were living on the streets of San Francisco, coming to terms with this thing that had terrified them all their lives. But in the process, they found it to be not as frightening as they first imagined.

Life is about relationships

Sean Illing

You said a minute ago that people, near the end of their lives, care more about their connections with other people than they do anything else. Why do you suppose that is?

Frank Ostaseski

I think that for a lot of people, religious traditions and spiritual practices are about relationships. That’s mostly where most people put their attention. That’s where they feel the greatest love. That’s where they learn the most. It’s where they feel the most value in their lives.

Death is a mystery, and people who are dying are turning toward mystery, and mystery is this unknowable territory, the land of unanswerable questions. To be a good companion, I have to be comfortable in that territory of mystery as well, and that doesn’t mean that I have all the answers. It means that I’m willing to stay in the room when the going gets tough. That I don’t turn away from the unknown, that I enter with a quality of curiosity and wonder.

Sean Illing

You had a serious heart attack not too long ago, and came close to dying yourself. Did that experience teach you something you couldn’t otherwise have learned about death?

Frank Ostaseski

Wow, that’s a really great question. Thank you for that. I don’t know that there’s one thing, but certainly it was humbling. It was humbling to see just how helpless I felt, how frightened I was. It’s not an uncommon thing after a heart attack for people to be sort of emotionally spent or to have depression — and I had all of those things.

Then there was this thing that happened for me, which is that I went from feeling vulnerable and dependent on others to feeling more relaxed and permeable. The fear slipped away. My default position started becoming something more like openness. Ultimately, I walked away with a much deeper understanding of compassion

“Grief is actually our common ground”

Sean Illing

It’s a great cultural failing that we don’t know how to be around death, and we don’t know how to be around people who have recently lost someone. Is this an American problem or a universal problem?

Frank Ostaseski

I don’t think it’s uniquely American, though it’s rampant here. It has to do with our rugged individualism and our fear of getting too close to pain. You know, your mother dies and you go to a party and nobody mentions it because we don’t want to upset you. What we do is we leave the person who’s grieving in isolation to deal with their pain or their grief unto themselves. Or we try to manage grief.

We have grief groups and bereavement groups which are terrific. That’s great that they’re there, but oftentimes we impose on the person who’s dying some kind of model about how they should move through their grief. Grief is totally unpredictable. It includes a whole constellation of experiences. Sadness is one phase of grief, but so is fear. So is numbness. So is relief. So is anger.

In some cultures, people used to wear a particular kind of clothing or a black armband to basically let everybody else know, “Look. I’m in an altered state here. Don’t expect me to behave normally. Help me grieve. Do my laundry for me. Help me fill out the insurance forms. Bring me food. Understand that I’m walking through the world in a very different way.”

I think that grief is actually our common ground. I think that so often we talk about it as the loss of something, like someone we love, for example. But I think also our grief is not just about what we’ve had and lost. It’s often about what we never got to have. I think there’s a lot of that floating around in the culture. There’s a kind of underground river that surfaces sometimes when there’s a death or a big loss shows up in our life.

We don’t have to be technicians. We don’t have to be psychotherapists. We can just be human beings and reach out in the darkness. Touch each other.

It’s so normal, Sean. That’s the thing. It’s just that we removed it from everyday life, and so we become frightened and we’ve forgotten what we know.

Dying can teach us to appreciate that everything is always changing

Sean Illing

What lessons do the dying have to teach the living about how to live better and well?

Frank Ostaseski

There are so many things, so I always am hesitant to sum it all up in a single response. I think the piece that’s become most apparent is of course what we just mentioned: Everything changes. When we fight against that truth, we suffer. That’s the first thing that they’ve shown me.

The second is that we’re all in this boat together. All of us are subject to this experience, so recognizing that causes us to be kinder to each other, and I think it causes us to not hold on to our desires so tightly. We let go more easily and this engenders a certain kind of generosity and gratitude in our life.

It’s all changing. Live in harmony with that. Be grateful for what’s here in front of us.

And love as hard as you can. Love just as hard as you can, because in the end, that’s what matters most.

Leave a Comment