For years, I’ve worked with people who are dying. Some of these people are very tough. They may have been living on the streets for a long time. They may be angry about their loss of control. Often they don’t have trust in humanity. Frequently they turning their heads to the wall in withdrawal or depression and don’t come back again. Most of them don’t care beans about Buddhism. If I am going to be of any use at all, I must be particularly clear and honest about my intention; if I’m not, they will quickly sniff out my insincerity and sentimentality.

Some of the individuals I work with blossom, and the way in which they die is a great gift; they make reconciliations with their long-lost families, and they find the kindness and acceptance they have been looking for their whole lives. It can be quite wonderful to be around these people. But I don’t do this work because it can turn out so well. Chasing such rewards brings exhaustion and ultimately leads to manipulation because we’re so busy trying to create the conditions that lead to a reward. In so doing we miss the current situation. I do this work because I love it and because it serves me. I try to see myself in each person that I serve, and I try to see them in me. Those I work with know and trust that, in fact they come to rely on it. We understand that we are in the boat together.

At the very heart of service, we understand that the act of caring is always mutually beneficial. We understand that in nurturing others we are always caring for ourselves, and this understanding fundamentally shifts the way we provide care. I’m not the good guy coming to the rescue; I have no white horses.

We become what I call ‘compassionate companions’. ‘Compassion’, when literally translated means ‘ suffering with others’ and the little word ‘with’ is so important, because it implies intimacy and belonging. ‘Companion’ is ‘one who travels with another’.

In the service relationship, there is no guide, there is no healer and no one healed; we simply accompany one another. As one Zen teacher put it, “We are simply walking through birth and death holding hands.”

Prior to any action of the body, thought, or speech, there is a moment of intention that we need to be aware of because clarity about our intention gives us choice about how we can proceed. A moment of contact with our intention can break our habitual patterns and keep us from operating on automatic pilot.

In the Zen tradition, there is a practice called dokusan. It is an interview with the teacher. The student is instructed to wait outside the teacher’s door, where they gather themselves completely into the moment. We have no idea what is waiting for them on the other side of the door. We have no idea what the teacher will ask, so we need to be ready, flexible and open. Going into a room of someone who is ill or dying is like going for dokusan. Ideally, our bodies and minds should enter the room at the same time.

Too often in care-giving, we’re not so much looking to see what serves but to confirm some idea we have about ourselves. We want to be somebody. We invest in the role. I sometimes call this ‘helper’s disease’, and it is a more rampant epidemic than Alzheimer’s or cancer. I’m speaking about the ways we try to set ourselves apart from other people’s suffering. We set ourselves apart through our pity, our fear, our professional warmth and even our charitable acts.

This attachment to the role of helper is familar to most of us; helping others provides a needed sense of power or respectability that we collect at the end of the week like a pay check. But if we’re not careful, this identity will imprison us as well as those we serve. After all, if I’m going to be a helper, somebody needs to be helpless!

My friend Rachel Naomi Remen MD, a pioneer in relationship centered care and the author of Kitchen Table Wisdom offers us another option.

She says:

“Service is not the same as helping. Helping is based on inequality, it’s not a relationship between equals. When you help, you use your own strength to help someone with less strength. It’s a one up, one down relationship, and people feel this inequality. When we help, we may inadvertently take away more than we give, diminishing the person’s sense of self-worth and self-esteem. Now, when I help I am very aware of my own strength, but we don’t serve with our strength, we serve with ourselves. We draw from all our experiences: our wounds serve, our limitations serve, even our darkness serves. The wholeness in us serves the wholeness in the other, and the wholeness in life. Helping incurs debt: when you help someone, they owe you. But service is mutual. When I help, I have a feeling of satisfaction, but when I serve I have a feeling of gratitude. Serving is also different to fixing. We fix broken pipes; we don’t fix people. When I set about fixing another person, it’s because I see them as broken. Fixing is a form of judgment that separates us from one another; it creates a distance.

“So, fundamentally, helping, fixing and serving are ways of seeing life. When you help, you see life as weak; when you fix, you see life as broken; and when you serve, you see life as whole. When we serve in this way, we understand that this person’s suffering is also my suffering, that their joy is also my joy and then the impulse to serve arises naturally – our natural wisdom and compassion presents itself quite simply. A server knows that they’re being used and has the willingness to be used in the service of something greater. We may help or fix many things in our lives, but when we serve, we are always in the service of wholeness.”*

Caring for those who are suffering can wake us up. It can open our hearts and minds. It opens us up to the experience of wholeness. When we are busy trying to protect our self-image, or hide behind a role or treasured belief we cut ourselves off and isolate ourselves from the wisdom that would inform our service. To be people who heal, we need to be willing to bring our passion to the bedside; our own wounds, our fear, our full selves. It is the exploration of our own suffering that allows us to form an empathetic bridge to the person. To touch their pain with compassion instead of fear and pity.

The degree we are willing and able to live in this ever-fresh moment is the measure of our ability to be of real service. When the heart is open and the mind is still, when our attention is fully in this moment, then the world becomes undivided for us and we know what to do. Each of us has that capacity. Each of us can to embrace another person’s suffering as our own. We have been doing it for hundreds of years-we’ve just forgotten how, and so we need to remind each other.

When the heart is undivided, everything we encounter becomes our practice. Service becomes a sacred exchange, like breathing in and breathing out. We receive a physical and spiritual sustenance in the world, and this is like breathing in. Then, because each of us has certain gifts to offer, part of -our happiness in this world is to give something back, and this is like breathing out. One friend calls this ‘simple human kindness’. Our work, I think, is to get out of the way of our own innate wisdom and compassion-that simple human kindness-and allow our inborn ability to see what another needs, to serve their dying and their living.

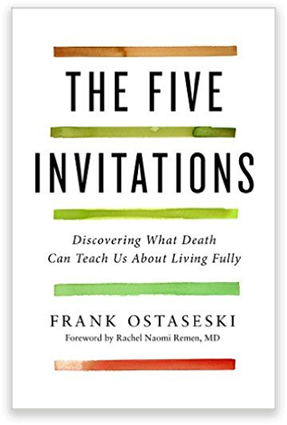

—Frank Ostaseski is the founder of the Metta Institute and cofounder of the Zen Hospice Project and author of Five Invitations: Discovering What Death Can Teach Us About Living Fully. www.fiveinvitations.com

Copyright Frank Ostaseski

*Quotation by Rachel Remen from the Noetic Science Journal

Leave a Comment